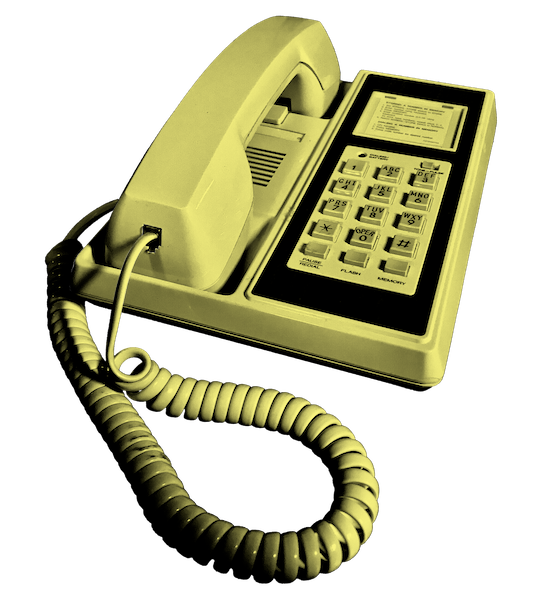

ISSUE 1: Landline

Coming 2026.

Every Object an Archive:

Exit interviews for aging technologies

One object at a time, we are conducting interviews with people about their experiences using once-ubiquitous technologies. These will take the form of ‘exit interviews’ for technologies (with users as a proxy for the objects themselves). First up, in early 2026, we will be exploring the landline telephone.

The interviews will be an opportunity for people to reflect on how technologies impacted their lives and consider – exit interview style – what should be improved, changed, or remain intact as new objects and processes take their place. It will also be an opportunity for us to think about potential interventions in the current and emerging technological and social landscape.

A technology is more than a physical object. Infrastructure, processes, policies and culture are built around them, and these affect our ways of being in the world, including how we carry out activities and communicate with each other. Our aim is to consider the processes, practices and cultural experiences that might be lost as a technology falls out of use. We also want to understand how people feel about these transitions.

We will produce a report for each object we explore with quotes, themes and analysis from the interviews, along with recommendations about how certain social or cultural practices might be retained even as the technology that engendered them falls by the wayside.

Every Object an Archive is a project of Antistatic, a research and communication consultancy led by Anna and Kelly Pendergrast. We are interested in the intersections of material culture, infrastructure, community practices, and technology — themes that will be explored throughout the course of this project. Get in touch if you’re interested in collaborating or want to learn more.

Background and context

Every technological object — from a ballpoint pen to the latest smartphone — contains its own universe. First, the physical materials that constitute the object, and manufacturing process and material development that contributed to its development. Beyond that, the uses to which the object were put, its life as a tool or a toy or a component. And finally, the clusters of behaviors that emerged around the object, as it shaped and was shaped by the ways people work and live and move through space. Every object is a history lesson, an archive, a lens.

Not every object lasts. New tools and technologies are developed, and these may be faster or cheaper or more efficient that what came before. An object that had been central to people’s lives for decades or centuries can suddenly find itself taking a back seat, superseded and eventually replaced by a new tool with its attendant materials and affordances and clusters of behavior. The landline declined in popularity as the cellphone became the dominant tool for long-distance communication. The horse and buggy was relegated to specialty status in most places after the automobile was popularized as an efficient mode of private transportation.

Many scholars have investigated the process through which technological change happens. It is not a natural or inevitable process, and is generally influenced by a range of forces from scientific development to capital investment to changing lifestyles. Usually, the transition from one technology to the next is not a one-to-one replacement. The cellphone is not just a wireless telephone, Netflix is not just an online movie theater, and a car is not a gas-powered horse — even if they initially appeared as such. We are not here to mourn these changes, nor to celebrate them. Instead, we are interested in the cultural behaviors and patterns of experience that might be lost in the transition from hand loom to steam loom, bank teller to banking app.

In the 2010s, it became a trend for technologists and marketers to talk about “bundling” and “unbundling” of services in order to sell customers and investors on their new innovations. Food delivery could be unbundled from the restaurant, for instance, and news could be unbundled from the newsroom. However, the restaurant and the newsroom both have their own universes of practice and convention and sociality (“bundles”, if you must), which may not be part of whatever they’re unbundled into.

Ultimately, there are better things to do than cry over spilled milk. The Palm Pilot is not coming back. However, we argue that there is value in documenting the behavioral and social world of objects as they are on their way out of popular use. What was it like to live with the landline? How did it shape your household, relationships, and sense of space? From there, we can consider what we might lose out on if these experiential bundles are no longer commonplace, and whether there are ways to revivify or reinsert some of these affordances into the current and emerging cultural and technological world.

We are indebted to the work of the many scholars in Science and Technology Studies, critical media studies, and other disciplines whose research informs our thinking on these topics. We look forward to being in dialogue with this existing scholarship, and bringing our own specific set of interests, influences, and obsessions into play as we make our own contribution to the conversation.

Contact us.

If you are interested in collaborating, commissioning a future issue, or speaking to us about Issue 1: Landline, please email us at hello@antistaticpartners.com. You can also sign up to receive occasional future updates about this project using the form to the right.